As a sequel to “Trump Truth,” this is a useful piece to read. Bloomberg Surveillance reported this morning that since Trump’s so-called “Liberation Day”, when his new tariff regime was impose, the economy has deteriorated. Trump, as always, says the opposite. But his claims contradict both the data and reality.

This contradiction is not accidental. It is the ruse. The economic narrative Trump overlays is grounded in the same corrupt ethos that defines his entire administration: not governing but controlling. Their goal is not “America First.” It is “America Foist”; impose chaos, then exploit it.

That same logic is now visible in law enforcement. The Minneapolis police chief has publicly stated that while he supports enforcing immigration law, the way federal agents are being deployed, especially ICE, violates basic professional standards and is fueling violence. He warned that the current federal strategy will not stabilize or protect but will ignite and escalate. One must ask whether escalation is not the objective, a pretext to justify even greater repression.

At some point, Americans will reach their limit watching fellow citizens have their rights crushed and even their lives taken by those sworn to protect them. Power has replaced public safety as the object of the federal government.

We see the same pattern in Trump’s latest move against the Federal Reserve Chair. On Friday, a Justice Department “investigation” was launched against the Fed Chair (Trump absurdly claims he knew nothing about but made the allegation during his July 2025 meeting with Powell touring the building = BS). The Chair has stated plainly that this is an attempt to weaponize law enforcement to punish a policy disagreement. A move Putin, Stalin and even Mussolini would be proud of. Senator Thom Tillis, the Republican chair of the Senate Finance Committee, has now said this is wrong and that he will block any new Fed chair until the matter is resolved.

That is the through-line of Trump Truth:

Facts are replaced with lies. Law is replaced with intimidation. And power is pursued not to serve the country — but to control it.

RESIST!!! & EDUCATE!!!

What have we learned?

JAN 11, 2026

Source: BLS

Note to subscribers: Last Sunday I said that today’s primer would finish my series on China’s trade surplus with a discussion of policy responses. But I’m going to postpone that post until next week, partly because I’m still working on some issues, partly because new data make this a good time to talk about how Trump’s economic policy is playing out.

Warning: This post contains a lot of charts.

Donald Trump is president again for one main reason: He promised a new age of American prosperity with lower prices, a shrinking federal deficit, and a resurgence in manufacturing jobs. Enough voters believed his promises to swing the 2024 election. But many of them are disillusioned now. Trump insists that he is actually delivering on his campaign promises, claiming that we have a “hot” economy. But voters don’t agree: Consumer confidence is low and Trump’s approval rating on handling the economy, which was strongly positive last January, is now strongly negative.

On Friday we received the final jobs report for 2025, so now is a good time to take stock of the results so farand assess how well Trumponomics is actually working. Let me not be coy: This is not a hot economy, by any objective measure. Granted, the U.S. economy isn’t falling off a cliff either. In fact, what we’re seeing isn’t a classic recession; it’s more a sort of creeping malaise.

In what follows I’ll try to keep it cool. Everyone knows my political views, but this will be a fact-based primer, not a polemic.

Beyond the paywall I’ll address the following questions:

1. How is the U.S. economy doing?

2. Why does the labor market feel so bad?

3. What is the stock market telling us about the economy?

4. How does economic performance so far compare with expectations?

5. Why aren’t we doing better?

6. Why aren’t we doing worse?

7. What will come next?

How is the U.S. economy doing?

Early every month the Bureau of Labor Statistics releases data on the state of the job market the previous month. The Employment Situation report is based on two surveys: a survey of employers and a survey of households. The employer survey produces, among other things, estimates of total employment. The household survey produces, among other things, estimates of unemployment.

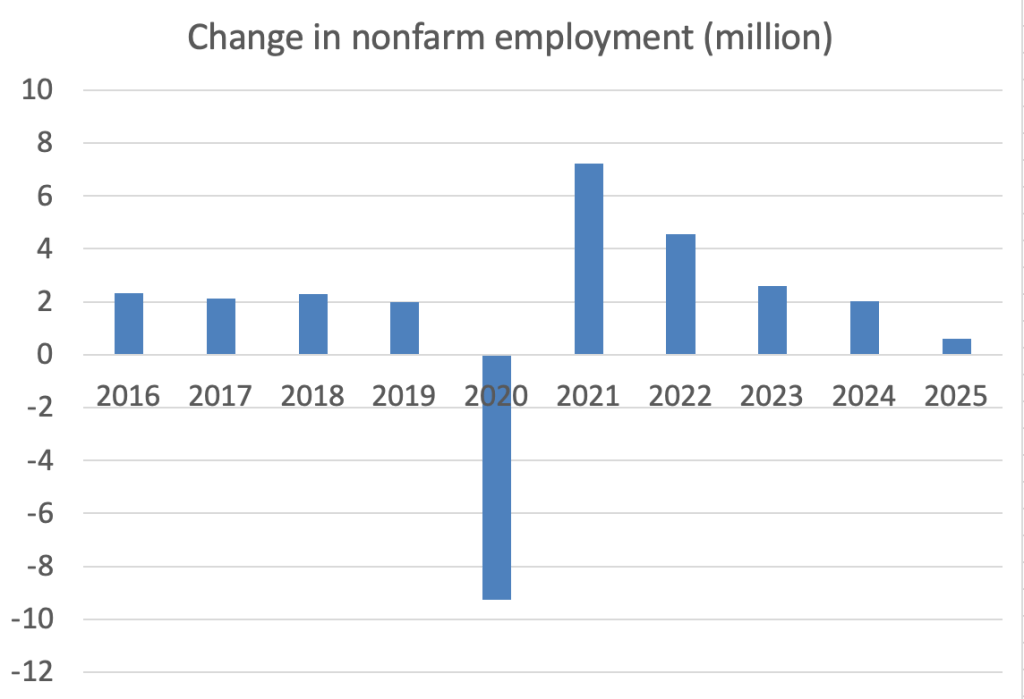

While these data are noisy on a monthly basis, last Friday’s final job report for the year smooths out the noise and gives us an assessment of U.S. job performance over 2025 as a whole. And it definitely wasn’t great. As the chart at the top of this post shows, job growth in 2025 was clearly weak. In fact, the year of the Covid pandemic aside, it was the weakest in a decade.

This is not a hot economy. Indeed, by multiple measures it’s notably worse than the economy Trump inherited from Biden.

And it may be even colder than reported. BLS employment numbers are often significantly revised when more comprehensive information comes in. Cognizant of that fact, Federal Reserve officials believe that recent BLS employment numbers may have been overstating job growth by as much as 60,000 a month. If that’s true,employment may have been flat for 2025 as a whole.

If the US is not gaining jobs, is it at least adding good jobs while shedding bad jobs? A Thursday night Trump Truth Social post appears to make this claim.

That Truth Social post represented an extraordinary breach of the rules for handling BLS reports. These reports, publicly issued at 8:30 AM on a Friday, are provided to the White House the previous night — but only on the strict condition that the information is to be kept confidential, with officials refraining from comment until half an hour after the public release. This rule is intended to prevent insider trading. Yet Trump’s Thursday post included job numbers that were under the disclosure embargo. So the post was illegal and would probably have led to jail time if a staffer had done it.

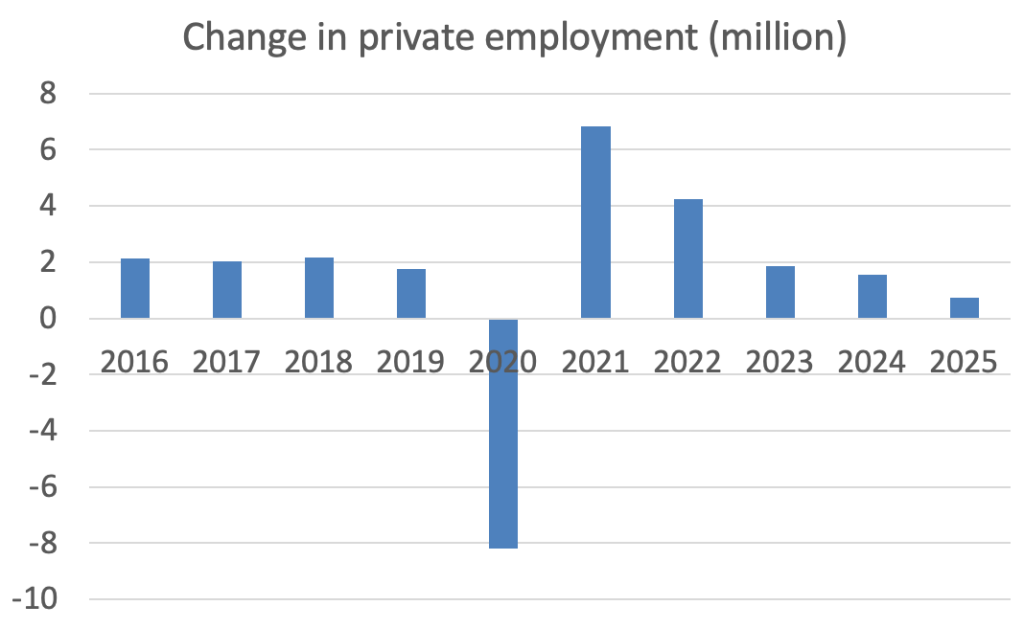

Trump’s intention was clearly to spin the report. He wanted to claim that weak employment growth in 2025 was partly a result of layoffs by DOGE, in which supposedly unproductive jobs were eliminated. However, it’s likely that Trump didn’t realize that this claim doesn’t make any sense — 2025 was a very weak year even if one only counts private-sector jobs:

Source: BLS

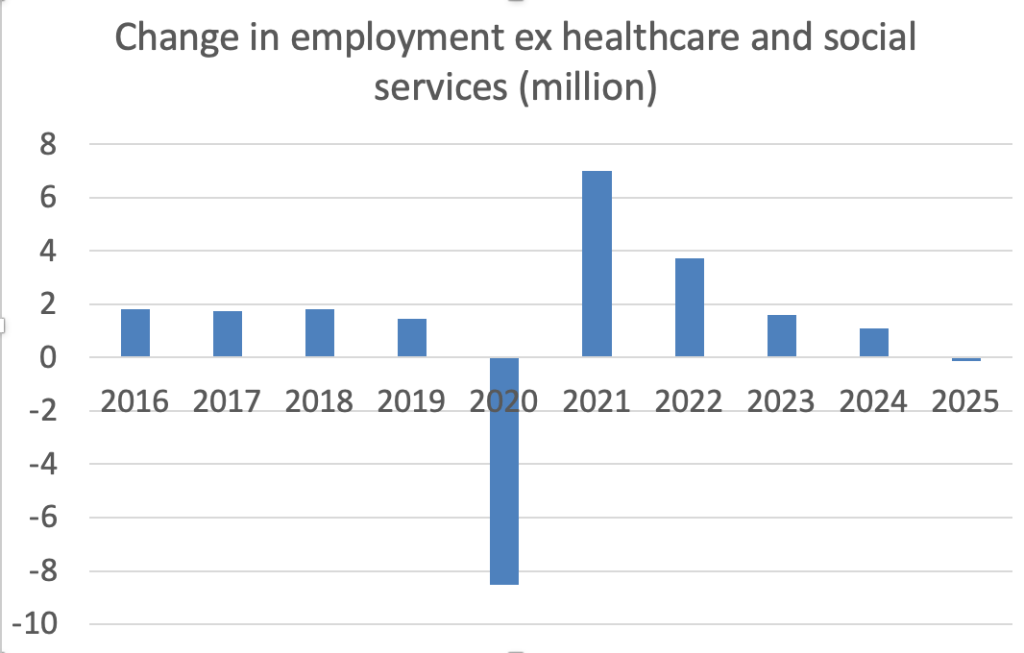

Similarly, Trump administration officials have suggested other definitions of what constitute “real” jobs in order to spin the weak employment numbers. For example, Scott Bessent, the Treasury secretary, has dismissed strong employment growth under Biden by saying that it was overwhelmingly government jobs or jobs in “government-adjacent” sectors like health care and education. But if your position is that government or government-adjacent jobs don’t count as “real jobs,” then 2025 looks even worse: All net job creation took place in health care and social services, with employment in the rest of the economy declining:

Source: BLS

I could go on. Joey Politano notes that 2025 was marked by a decline in blue-collar jobs, aka “manly” jobs — basically jobs that might possibly require upper-body strength. There is simply no plausible way to slice and dice the data to make the 2025 job creation numbers look good.

That said, weak job growth didn’t lead to a huge rise in unemployment. The BLS defines unemployment as the number of people who are actively seeking work but don’t currently have a job — a number that is estimated using its monthly survey of households. The unemployment rate rose during 2025, but only from 4.1 to 4.4 percent. This was a significant rise, but not enough to trigger the widely used Sahm rule indicator (originally devised by Claudia Sahm, who I interviewed early in 2025), which generally signals that a recession has begun.

Why didn’t unemployment rise by more? As I will discuss later, Trump administration policies have reduced the demand for labor. These policies are probably the main reason job growth has declined so much. But the combination of a crackdown on new immigration and deportation of people already in the United States has simultaneously reduced the supply of labor, and thereby reduced “breakeven employment growth,” the number of jobs the economy needs to create each month to keep unemployment from rising. In effect, without the crackdown on immigration and deportations, it’s likely that the unemployment rate would have risen substantially.

It’s important to understand that I am not saying that anti-immigrant policies have been good for native-born workers. They suffered rising unemployment over the course of 2025. I’m just trying to explain the mechanics here — how very weak job growth in the Trump economy is consistent with only a moderate rise in unemployment.

Why does the labor market feel so bad?

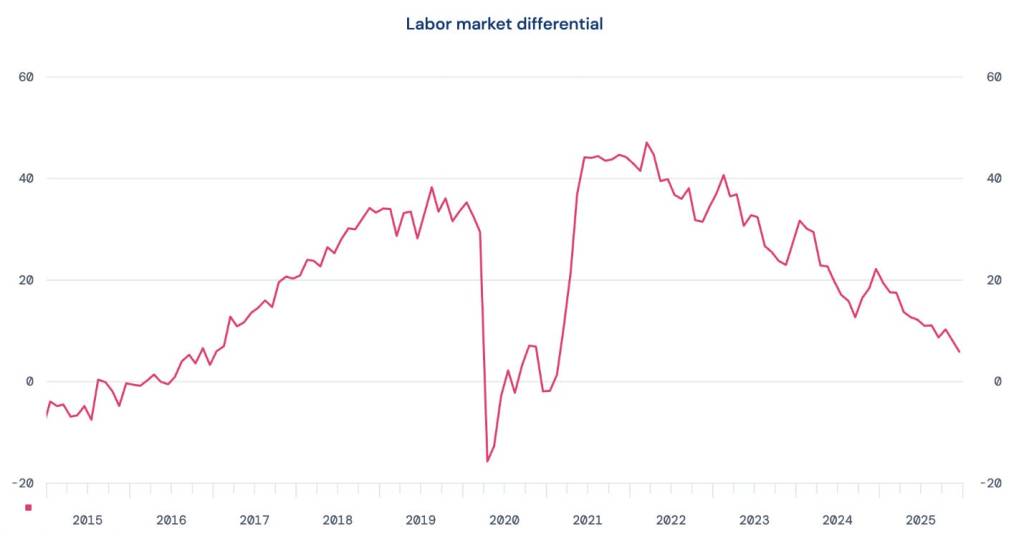

Official unemployment numbers aside, American perceptions of the state of the jobs market deteriorated sharply during 2025. For example, The Conference Board, which conducts a monthly survey of consumers, reports a measure called the “labor market differential” — the difference between the number of people saying that jobs are “plentiful” and those saying jobs are “hard to get.” While this measure turned upwards during the last quarter of 2024, it has turned sharply downward since then:

Source: Conference Board via Haver Analytics

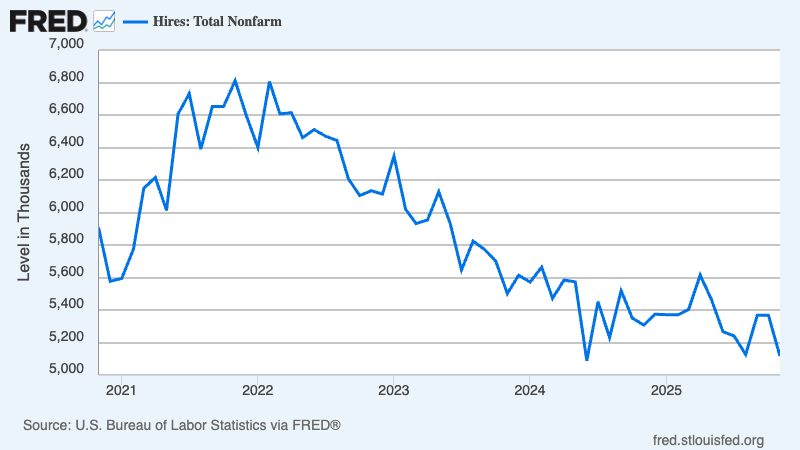

But there weren’t mass layoffs in 2025. So why have perceptions of the state of the labor market deteriorated? Because while companies aren’t engaging in mass firing, companies also aren’t doing much hiring. As you can see in the chart below, starting in the spring of 2025 total nonfarm hires began falling:

Low hiring by employers makes it really hard to find a job. So public perceptions of a difficult job market are grounded in reality.

Because it’s hard to find a job, long-term unemployment — the number of people who have been unemployed for 15 weeks or more — has risen much more than total unemployment. This is a particularly bad outcome because extended unemployment is much more harmful to workers and their families than brief periods of joblessness. In addition, the weak job market hurts workers who are employed, because it reduces their bargaining power: It’s risky to demand higher wages or better working conditions when both you and your boss know that you will have a hard time finding a new job if you quit or are fired.

What is the stock market telling us about the economy?

Labor market data paint a dreary picture of the Trump economy so far. However, the stock market is up: The S&P 500 index rose 16 percent over the course of 2025. Doesn’t the stock market’s performance refute pessimism about the economy?

No, for three reasons.

First, the stock market isn’t the economy. Nor is it a good predictor of the economy’s future. Paul Samuelson famously quipped a long time ago that the stock market had predicted nine of the past five recessions; the joke still works.

Second, recent movements in overall U.S. stock prices have been dominated by a handful of tech companies, mainly the “Magnificent Seven,” that are being buoyed by enthusiasm about AI. Whether or not AI is a bubble, this narrowly based stock rally doesn’t tell us much about the broader economy.

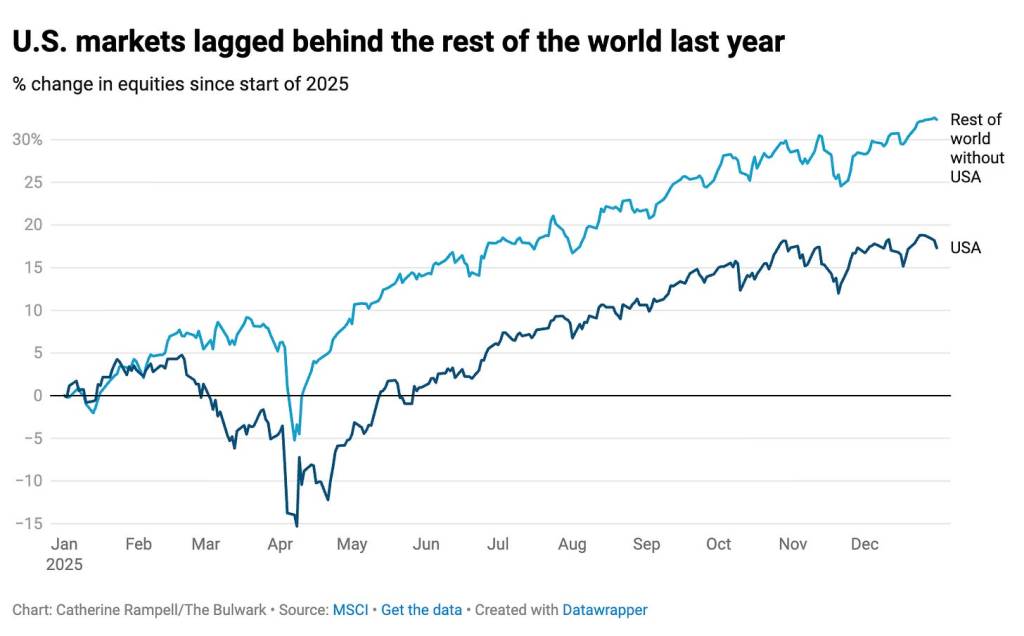

Third, stocks are way up all around the world. In fact, a global index that excludes the United States is up much more than U.S. stocks. I’m going to steal a chart from an excellent post by Catherine Rampell:

Source: The Bulwark

Why are stocks up around the world? Market commentaries say that investors are “risk-on,” which is almost a tautology: Investors are buying stocks because they’re buying stocks. Whatever is going on, however, it’s hard to say that rising stock prices are a vindication of Trumponomics when stock prices have risen much more in nations that aren’t ruled by Trump than in the nation that is.

The bottom line is that the weak job market, not the strong stock market, is the indicator to look at to assess how Trumpian economic policies are working.

How does economic performance so far compare with expectations?

During the 2024 campaign Trump promised an economic miracle. Since taking office he has repeatedly claimed that this miracle is indeed happening. But as we’ve seen, both hard data and public perceptions contradict his predictions and his claims.

On the other hand, did Trump’s critics overstate their case? I’ve seen many, many articles asserting that economists predicted that Trump’s tariffs would cause economic catastrophe, and that the failure of that catastrophe to materialize represents a big analytical failure.

But did Trump’s critics predict catastrophe? I’m sure that some did. But such predictions didn’t reflect what standard economic models say about the effects of tariffs.

Here’s what I said to Ezra Klein back in April 2025, just after Trump announced his massive Liberation Day tariffs:

There’s a funny thing here, which is that ordinarily I would say that while tariffs are bad, they don’t cause recessions. It makes the economy less efficient. You turn to higher-cost domestic sources for stuff, instead of lower-cost foreign sources, and foreigners turn away from the stuff you can produce cheaply. But that’s a reduction in the economy’s efficiency, not a shortfall in demand.

What’s unique about this situation is that the protectionism is unpredictable and unstable. And it’s that uncertainty that is the recessionary force.

That doesn’t sound to me like a prediction of economic catastrophe, and it wasn’t intended as such. Standard economic models do not say that tariffs will cause a severe recession, and economists who asserted otherwise were getting over their skis. I have been careful all along to say that the short-term economic drag from Trumponomics has come from policy uncertainty, not a recessionary impact from tariffs per se. And while the effects of policy uncertainty are clear, putting a number to them is a speculative venture given that the United States has never seen government policy this erratic.

In particular, it’s hard to incorporate the effects of uncertainty into quantitative models. What we can say is that economists who disciplined their predictions about Trumponomics with such models were circumspect in their assessments of negative impacts.

For example, I’ve relied a lot on analyses by the Yale Budget Lab, which has been producing projections of the effects of the Trump tariffs updated in the face of policy twists and turns. Their May 12 update said that the tariffs would raise the unemployment rate at the end of 2025 by 0.4 percentage points relative to what it would otherwise have been. This doesn’t look like an outlandish claim given that the actual unemployment rate rose 0.3 points in 2025. Also, bear in mind that effective tariffs in practice have been lower than headline numbers would suggest, a point I’ll get to in a minute.

I’m not saying that mainstream economists got everything about Trumponomics right. Most of us have been surprised at the slowness with which tariffs have been passed on in the form of higher consumer prices, a topic I won’t address in today’s post. But if we want to assess the accuracy of economists’ predictions, it’s important to focus on what they actually said rather than adopt a lazy narrative about everyone predicting utter disaster.

And if you do that it’s obvious that there’s no equivalence between the utter falsification of Trump’s claims and the modest predictive failures of Trump’s critics.

Why aren’t things better?

Trump’s grandiose claims about what his policies would achieve never made sense. But Trump’s tariffs did offer some industries a lot of protection against foreign competition. Why didn’t manufacturing employment expand, at least somewhat? And why has hiring plunged, leading to a very bad job market?

A large part of the answer to the first question is that international trade in the 21st century works very differently from the way trade worked in the 1890s, when William McKinley imposed the tariffs Trump admires. At the end of the 19th century nations basically traded final goods that were sold to consumers. In 1890 America basically exported agricultural products while importing manufactured goods, end of story. But modern trade is dominated by “value chains” in which most imports are inputs into the production of other goods.

Given this reality, Trump’s tariffs actually made U.S. manufacturing less competitive against foreign products, because the tariffs raised the cost of imported inputs. In the end, the loss of competitiveness due to the higher cost of imported inputs more than offset the benefits of protection from import competition that the tariffs provided.

And even as manufacturing has suffered from higher costs, U.S. farmers — who are highly dependent on export markets — have been severely hurt by foreign retaliation.

The answer to the second question — why hiring plunged — surely rests upon the extreme uncertainty that Trump created. Trump didn’t just impose high tariffs and maintain them. Instead, tariff rates on individual trading partners fluctuated wildly over the course of 2025. For example, the average tariff on imports from China began the year at 20 percent, rose as high as 130 percent, then ended the year at 47 percent. Nobody could be sure what would come next. In fact, right now businesses are anxiously waiting for the Supreme Court to rule on the legality of the Trump administration’s use of the International Economic Emergency Powers Act to impose a wide range of tariffs. It clearly was illegal; but given how permissive this Court has been towards Trump, it’s anyone’s guess how they will decide.

In the face of this unprecedentedly high level of uncertainty, companies are reluctant to make any kind of financial commitment, including the commitment involved in hiring new workers. Even if hiring a new worker today makes sense given the current tariff rates, an employer is reluctant to hire because tariffs next month or next year may be radically different from what they are today.

I will concede that the AI boom may have also contributed to the freezing of the labor market. In some cases companies don’t feel that they need new workers go because they can use generative AI instead. But what is probably more important in the freezing of the labor market is the anticipation that fewer workers will be needed in the near future due to AI, thus making companies unwilling to hire workers now.

So I won’t claim that Trumponomics is the sole reason for the bad job market. But it’s surely a major factor.

Why aren’t things worse?

I’ve tried to debunk claims that economists as a group predicted that Trump’s policies would cause economic catastrophe. It is, however, fair to say that the negative economic effects have been more muted than many expected. This is especially true for consumer prices, which I’ll address in another post, probably later this week. But it’s also true to some extent for employment.

An important reason Trump’s tariffs have had a smaller impact than many expected is actions taken by importers. In many cases, importers have found ways to avoid paying tariffs and, as a result, the average tariff rates actually paid are much less than the official rates.

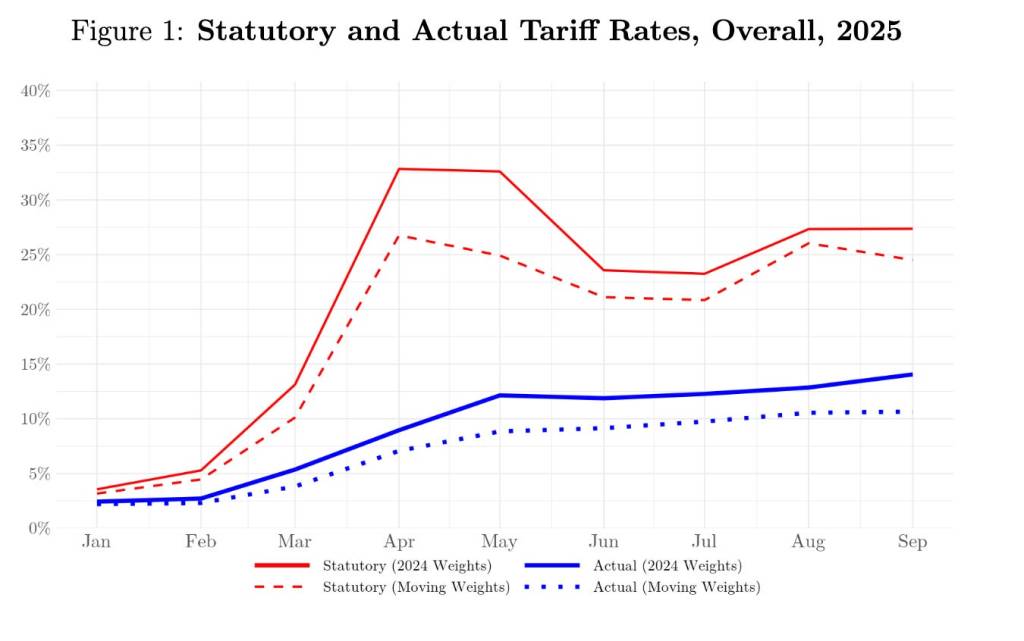

A recent paper by Gita Gopinath and Brent Neiman compares statutory tariff rates (red lines) — the official rates announced by U.S. authorities — with actual rates (blue line), measured by the ratio of tariff revenues to imports (ignore the dotted lines):

Source: Gopinath and Neiman

Why the big divergence between the statutory tariff rates and the actual tariff rates? It’s a matter of the fine print in tariff laws — fine print that corporations are exploiting now that tariffs are so high.

A prime example is trade with Canada and Mexico. We have a free trade agreement, the USMCA, with our neighbors. Under this agreement Canadian and Mexican exports to the United States can enter duty free if the importer can show that they are “USMCA compliant.” But proving compliance involves a lot of costly paperwork, which many companies didn’t bother completing when tariffs were low across the board.

Once Trump drastically raised tariffs, the cost-benefit calculus changed, and companies rushed to qualify for the tariff exemption:

Source: Penn Wharton Budget Model

The result of this and other maneuvers to bypass tariffs has been to limit the rise in effective tariff rates, which in turn has limited the adverse effects of Trump’s tariff spree.

However, it’s important to note that the costs associated with bypassing tariffs are much more easily borne by large companies than small companies. Moreover, large companies have been able to lobby the administration to get outright exemptions. Small companies, on the other hand, don’t have the political heft or the size to engage in these workarounds. So the burden of Trump’s tariffs has fallen far more heavily on small companies than on large companies.

There’s another factor limiting the damage from tariffs: the AI boom. I’ve suggested that this boom may have discouraged some companies from hiring. At the same time, however, huge spending on data centers is an important stimulus to the economy. This boom has nothing to do with Trump policies, but is a powerful force shaping the economy at the same time. Unfortunately, history doesn’t do clean experiments in which only one thing at a time is changing.

Some economists have argued that we would already be in a recession if not for the AI boom. This isn’t completely clear, but it’s certainly true that the AI boom has helped mask the adverse effects of tariffs.

What comes next?

Donald Trump returned to the White House with only one major economic policy idea: Tariffs, which he claimed would solve all the country’s economic problems, from reviving manufacturing to bringing down the federal debt. But his big idea has been mostly a big bust, hurting the economy, shrinking the manufacturing sector, punishing small businesses, farmers and rural America.

It’s true that the U.S. economy did not implode in 2025. However, it performed badly enough, especially for workers seeking jobs, that a different president would ask why and reconsider his policies. But Trump clearly won’t do that. He’s obsessed with tariffs, and in general his response to evidence of failure is denial and doubling down. So his failed tariff policy will continue unless the Supreme Court voids it.

Furthermore, tariffs aren’t working for him politically. And the voters who believed his promises are feeling angry and betrayed. So what comes next? Trump is clearly flailing: veering from declaring affordability concerns to be a Democratic hoax, to serving up a series of half-baked, unworkable policy initiatives — such as driving down energy prices with Venezuelan oil (except the oil companies aren’t interested) and capping interest rates on credit cards.

At the same time he is continuing to inject high amounts of uncertainty into the economy – trying to strip Democratic states of federal aid, canceling nearly completed green energy projects, ignoring the loss of health insurance for hundreds of thousands of people and the attendant financial hit to hospitals, and the economic hardship his trade war has created in export-dependent rural America. In addition, he threatens to destabilize financial markets by politicizing the Federal Reserve in his drive to force it to ignore inflation risks and drastically cut interest rates.

To conclude, Trumponomics 2025 is a story of how Trump worsened the economy that he inherited from Biden through big promises and policy choices that failed to understand how the economy actually works. The uncertainty created by Trump’s constantly changing tariff policy during 2025 appears likely to continue, as he delivers a stream of unworkable, half-baked ideas. While the stock market may be doing well, the rest of America isn’t. And it may very well get worse before it gets better.

Leave a comment